Costa Rica’s Green Legacy: Lessons in Sustainability, Renewable Energy, and Regional Resilience

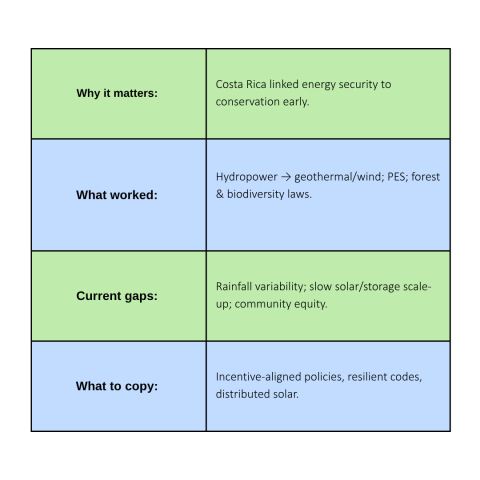

Costa Rica has long stood out as one of the world’s greenest nations, a global reference point for sustainability, renewable energy, and climate leadership. From early investments in hydropower to pioneering environmental laws, the country has built a reputation as a living laboratory for climate resilience. Yet as the conversation with Carlos and Jose Dengo of CDG Environmental Advisors reveals, sustaining this leadership requires constant innovation, regional collaboration, and openness to new approaches.

This article explores Costa Rica’s unique path, the challenges it faces, and the lessons it offers for Latin America and beyond.

Foundational Values and Policies: Building a Green Republic

Costa Rica’s sustainability journey is rooted in history. After a period of political upheaval in 1948, the country entered what is often called its “Second Republic,” a golden era of planning and institution-building. Through ICE (the national utility) and MINAE, Costa Rica linked electrification, watershed conservation, and social access, creating a solidarity-based model that reached even remote communities. Several foundational decisions laid the groundwork for the nation’s environmental leadership:

- Hydropower and renewable energy: Starting in the 1950s, Costa Rica harnessed its abundant rivers for hydropower. By the 1970s and 1980s, it had begun exploring geothermal and wind energy—long before “renewables” were seen as a climate imperative.

- Public, solidarity-driven utilities: Energy and communications infrastructure were developed under state-led models, ensuring electricity and connectivity reached even remote communities. This fostered equitable development and embedded sustainability in national priorities.

- Environmental protections linked to energy security: Protecting watersheds feeding hydropower dams led to the creation of early national parks, aligning conservation with economic growth.

Later, a trio of landmark laws cemented Costa Rica’s environmental identity:

- General Environment Law (1995) – guaranteeing a clean and healthy environment as a constitutional right.

- Forestry Law (1996) – prohibiting land-use change for areas classified as forest, catalyzing widespread reforestation.

- Biodiversity Law (1997) – protecting ecosystems, wetlands, and wildlife with an integrated approach.

*For more on Biodiversity in Costa Rica listen to the podcast episode

These reforms, coupled with the nation’s famous tourism slogan, “Costa Rica: No Artificial Ingredients,” helped brand the country as a green destination, tying environmental stewardship directly to economic prosperity.

A Family Legacy in Renewable Energy

For Carlos and Jose, Costa Rica’s green foundations are also personal. Their grandfather, Jorge Manuel Dengo, was a civil engineer who studied at the University of Minnesota in the 1940s. Inspired by U.S. hydropower systems, he returned to Costa Rica to co-found the Instituto Costarricense de Electricidad (ICE), the state utility that electrified the nation and ensured universal access to clean energy.

His vision—that energy development should also serve social equity—remains central to Costa Rica’s solidarity-based model. Their father continued this legacy through a career at the United Nations focused on water development. For Carlos and Jose, stepping into environmental consulting was a natural extension of this family tradition of linking natural resources, infrastructure, and social well-being.

Regional Influence: A Model for Latin America

Costa Rica has often “punched above its weight” in shaping regional and global sustainability agendas. At the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, it was among the first to champion ambitious environmental policies. Soon after, it pioneered carbon trading, signing an agreement with Norway that funded innovative conservation programs such as the Payment for Environmental Services (PES) scheme.

Through PES, farmers were compensated to preserve or restore forests, transforming a nation once plagued by deforestation into one where tree cover now thrives. Costa Rica’s diplomatic and technical leadership continues, as seen in global initiatives like the “30 by 30” ocean protection pledge.

The lesson for neighbors? Leadership requires both bold legislation and practical mechanisms that align economic incentives with ecological goals. Yet, as Carlos cautions, influence must be renewed through action—“to remain a leader not only on paper.”

The Shifting Landscape: From Compliance to Strategy

Across Latin America, companies are moving beyond compliance toward more strategic approaches to sustainability. According to Jose, this shift is partly driven by multinational corporations bringing global practices into local contexts, and partly by market differentiation: sustainability sells. Adopt a simple litmus test: if a claim can’t be traced to policies, performance data, or third-party standards, it’s marketing—not strategy

But the path isn’t always smooth. Some firms mistake marketing claims for meaningful action, while others bristle when assessments reveal gaps in their strategies. Practitioners play a critical role in separating substance from “greenwashing” and guiding businesses toward authentic, integrated sustainability.

This evolution reflects a broader regional challenge: moving from improvisation and fragmented benchmarks to structured frameworks that elevate corporate responsibility across industries.

Businesses exploring how to adopt renewable energy at scale should see our article on the Just Energy Transition.

Climate Risks and Sectoral Responses

Costa Rica’s resilience story also carries cautionary notes. Its once-robust hydropower system, a pillar of national pride, now faces strain from climate variability. Rainfall patterns are increasingly unpredictable—short, intense storms replace steady seasonal rains—threatening water storage and energy reliability. Without scaling solar and wind, the grid risks losing its competitive edge.

The tourism sector demonstrates how sustainability can be both an asset and a tension point. Luxury eco-lodges and conservation-driven models attract international visitors and support biodiversity restoration. For example, one project is creating a scarlet macaw rehabilitation center to reintroduce the species to areas where it had gone locally extinct. The brilliant red, yellow, and blue birds not only restore ecosystems but also become a powerful draw for visitors. Yet the exclusivity of luxury tourism risks leaving local communities behind, making equitable benefit-sharing essential.

In agriculture, climate volatility is forcing adaptation. Rice farming is increasingly uncompetitive under shifting rainfall patterns, while coffee faces disease pressures such as leaf rust triggered by alternating humidity and heat. Farmers are turning to crop rotation, fallowing, and diversification to survive—measures that showcase both the vulnerability and adaptability of rural livelihoods.

Water infrastructure is another critical fault line. In Guanacaste, for instance, communities have clashed with large tourism projects over water scarcity. As Carlos noted, the issue is often not the lack of water itself but inadequate infrastructure to deliver it consistently. Without trust-building and transparent communication, such tensions can escalate, threatening both community well-being and investment viability.

The overarching lesson: resilience is not static. Success requires constant innovation, reinvestment, and attention to equity.

Regional Collaboration: Toward a Shared Resilience Framework

Central America is among the most climate-vulnerable regions in the world, facing hurricanes, tropical storms, earthquakes, and volcanic activity. For Jose, the answer lies in regional collaboration. Just as Costa Rica’s seismic building code has minimized earthquake damage, a regional climate-resilient infrastructure code could help safeguard public assets from increasingly extreme events.

Such standards would protect taxpayer-funded infrastructure, reduce economic losses, and build collective resilience. Cross-border collaboration is also vital for managing shared ecosystems and watersheds, which do not adhere to national boundaries.

Emerging Trends: Technology, Solar, and Social Engagement

Looking forward, two trends stand out:

- Solar and storage: With abundant sunshine year-round, Central America is uniquely positioned to expand distributed solar generation. Lower costs and better battery technologies make this a transformative opportunity for both energy security and equity.

- Community and social engagement: Traditional models treated social concerns as peripheral. Today, communities are informed, vocal, and mobilized. Social license is as critical as regulatory permits, requiring genuine, early, and ongoing engagement.

Technology, including AI-driven analytics, can enhance problem-solving and solution-scaling. As solar and wind grow, it’s critical to pair deployment with responsible planning, such as via EIAs — see our article Harnessing Renewable Energy Responsibly. As Carlos emphasizes, innovation must be paired with social sensitivity—listening to communities as partners rather than obstacles.

Advice for Companies: Open Minds and Long Journeys

For companies accelerating their sustainability journey in Costa Rica or the broader region, Carlos and Jose offer two key pieces of advice:

- Enter with humility and openness: Multinationals must adapt to local contexts. What works in California or the Philippines may not apply directly in Central America. Listening to communities and advisors builds trust and ensures alignment with real needs.

- Embrace sustainability as a journey, not a destination: Progress is incremental. Ambitious goals are important, but real transformation comes through continuous improvement, iteration, and cultural integration over time.

Conclusion: Costa Rica’s Living Laboratory

Costa Rica shows that sustainability is not the result of one policy or program, but a tapestry of history, values, institutions, and innovation. Its story underscores the power of bold legislation, the importance of community trust, and the risks of complacency in a changing climate.

For the region and the world, Costa Rica offers both inspiration and warning: leadership in sustainability is never “finished.” It is earned, renewed, and strengthened with each new challenge. The global community can learn from Costa Rica’s successes and struggles alike—adapting its lessons in energy, tourism, agriculture, and governance to build a more resilient future for all.

Inogen Alliance is a global network made up of over 70 of independent local businesses and over 6,000 consultants around the world who can help make your project a success. Our Associates collaborate closely to serve multinational corporations, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations, and we share knowledge and industry experience to provide the highest quality service to our clients. If you want to learn more about how you can work with Inogen Alliance, you can explore our Associates or Contact Us. Watch for more News & Blog updates, listen to our podcast and follow us on LinkedIn.